How digital rights and awareness can fight dynamics of control

In October 2017 a Palestinian construction worker posted into his Facebook account a picture of himself at work, near a bulldozer. In the caption he wrote “Good Morning!”. Facebook algorithm made a translation error from Arabic into Hebrew, and it translated “Hurt them”. The man was immediately arrested as a suspect of terroristic activities, until police eventually realised the mistake, but the post was still taken down: you are never too careful.

(Harari, 2018)

The ambivalent nature of the Internet is perfectly described by Galloway, who sees it as “a delicate dance between control and freedom”. Internet is in fact a world where effective democratic empowerment coexists with danger of digital control and surveillance by both state and commercial actors. Corporation-owned social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp make no exception and are perhaps the place where these threats are most worrying, due to the very sensitive nature of the information exchanged there.

Since people use social media to shape and build their identity, showcasing their ideas, actions, believes and civic engagement, the object of potential surveillance in that space is life itself. By controlling or collaborating with these platforms state and corporate forces could directly access and control a huge amount of private data about real, identifiable individuals. The entity of these networks of datified selves also contributes to making such scenario even more disturbing: for instance, in the first months of 2020 Facebook reported circa 3 billion users, amounting to 38% of the world population.

To date there is an alarming lack of international legislation and regulation addressing digital rights and the threats of digital surveillance by state actors. For those who live in a “democracy”, this lack might seem innocuous (even if events like Brexit proved the contrary), but some examples around the world show us how this legislative deficit, when combined with certain political and social conditions, can have dramatic turnouts.

The case of Palestinian users offers a disturbing example of society of (digital) control where government and tech companies join forces to monitor and control citizens’ lives and civic engagement.

Theoretically, Israel’s signature of the ICCPR [1] constitutes a legal obligation to protect and preserve basic human rights, such as privacy and freedom of speech and assembly. However, Israel, joined by the Palestinian Authority and Hamas, systematically violates Palestinian’s digital and human rights engaging in practices of digital surveillance, censorship and oppression, with some degree of collaboration by social media corporations such as Facebook.

As reported by Adalah, the Israeli Cyber Unit has been issuing requests to social media platforms to take down specific content, especially targeting Palestinian journalists and activists. According to 7amleh (2020), in 2019 there were more than 1000 Palestinian content takedowns across several platforms, including pages, accounts and groups across several platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp and others. Following widespread outrage, Israel argued that those requests don’t constitute an exercise of governmental authority, but are simply “voluntary requests”, attributing the ultimate decision to social media companies. This marks an alarming precedent where tech companies as private actors can shape and take part in governance dynamics, usually reserved to official authorities.

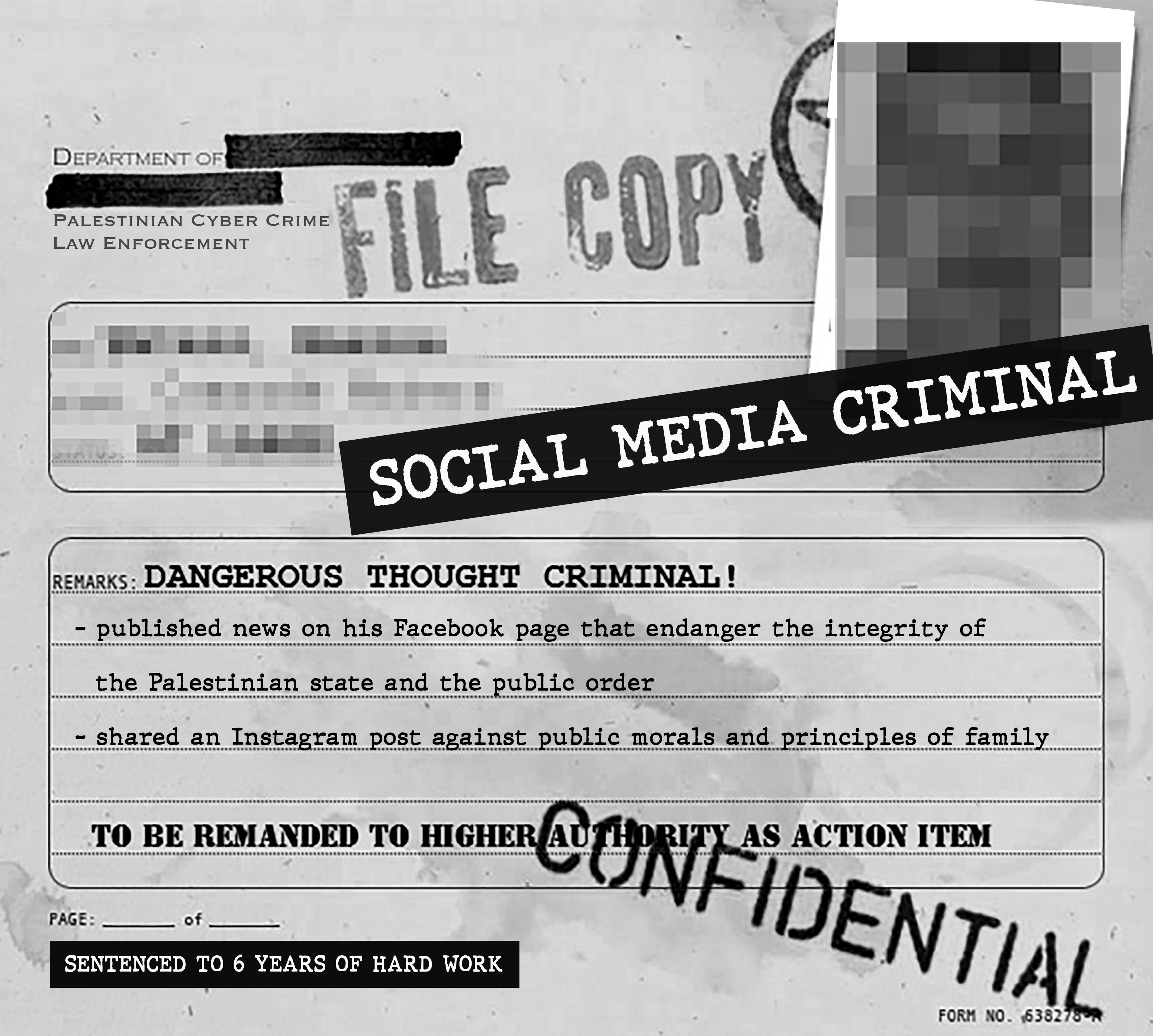

Unlike the State of Israel, the Palestinian Authority does not bother hiding behind presumed “voluntary requests”, but rather proudly enforces the so-called Cybercrime Laws, which led to the censorship of 100 Palestinian websites so far. Unsurprisingly, the provisions contained in these laws are often loose and vague, allowing the authorities to profit from broad interpretations of words such as “incitement” to arrest people due to their use of social media. Only in 2019, 5500 Palestinians were convicted merely due to their social media activity. Hamas has similar laws as well, criminalising the so-called “misuse of technology”, that justified the arresting of more than 1000 people during demonstrations in 2019. This regime of censorship and persecution had also a chilling effect on the population, especially on young Palestinians using online activism for political participation, leading to increased self-censorship and self-deterrence for fear of suffering even greater violations of their rights.

Given all this, the development of strategies of resistance can play a crucial role for Palestinian citizens and people under similar oppressive conditions. In recent years activists, organisations and scientists have joined forces to create alternatives to traditional social media, designed to make dynamics surveillance and control if not impossible, at least very difficult. Most emblematic examples include radically decentralised alternatives such as Twister or Soup, where data are not centrally stored and managed but are distributed across several private servers and hence more difficult to access and control.

Beside technical solutions the work and advocacy of activists and organisations can also play a huge part in encouraging counter-conduct and better media awareness among oppressed citizens. The Arab Centre for the Advancement of Social Media is a non-profit organization “protecting the human rights of Palestinians in the online space”. Not only it monitors (digital) rights’ violations, but also offers trainings and workshops in digital security and organises awareness campaigns.

Fighting the consequences is crucial, but we can’t stop there. We must act in advance, and fast, in order to prevent such situations from happening in the first place. We are in strong need for international regulations protecting digital rights, which should be handled as an extension of human rights in the digital domain. Such regulations could empower individuals while limiting practices of digital control and surveillance by both state and commercial actors. However, to achieve this there is something fundamental we need first: digital literacy, fluency and a common awareness as digital citizens. Only by understanding the digital world, its functioning and its driving forces and our huge power in it, we can finally advocate and fight for what is rightfully ours.

– Giada Severini

References

7amleh. (2020). Hashtag Palestine 2019: An Overview of Digital Rights Issues in Palestine. Retrieved July 2, 2020, from https://7amleh.org/storage/Hashtag_Palestine_2019_English_20.4.pdf

Barassi, V. (2016). Datafied Citizens? Social Media Activism, Digital Traces and the Question about Political Profiling. Communication and the Public, 1(4), 494-499.

Galloway, R. A. (2004). Protocol: How control exists after decentralisation. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Harari, Y. N. (2018). 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Vintage. 81-82.

Harcourt, B. L. (2015). Exposed: Desire and Disobedience in the Digital Age. Harvard University Press.